- Home

- Tom Llewellyn

The Shadow of Seth

The Shadow of Seth Read online

The Shadow of Seth

Tom Llewellyn

tomllewellyn.blogspot.com.com

Poisoned Pen Press

Copyright

Copyright © 2015 by Tom Llewellyn

First E-book Edition 2015

ISBN: 9781929345199 ebook

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in, or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

The historical characters and events portrayed in this book are inventions of the author or used fictitiously.

Poisoned Pen Press

6962 E. First Ave., Ste. 103

Scottsdale, AZ 85251

www.poisonedpenpress.com

[email protected]

Contents

The Shadow of Seth

Copyright

Contents

Dedication

Acknowledgments

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-one

Twenty-two

Twenty-three

Twenty-four

Twenty-five

Twenty-six

Twenty-seven

More from this Author

Contact Us

Dedication

This one’s for the boys:

Ben and Abel Llewellyn

Acknowledgments

Thanks to my talented editor at The Poisoned Pencil, Ellen Larson, for loving YA mysteries and liking this one enough to introduce it to the world. Thanks to my agent, the esteemed Abigail Samoun, for knocking on doors until Ellen finally answered. Thanks to Ben Llewellyn for helping me create Seth’s soundtrack. Thanks to Sweet Pea Flaherty, for being a character in real life and for loaning his name to a character in this book. Thanks to my dear friend Lance Kagey for lending his design talent to the cover. And finally, thanks to my beloved city of Tacoma, for letting me set a murder within its city limits.

One

Nadel called my cell phone just as I got home from school, asking if I could make a pickup. Mom was sleeping. She wouldn’t need her car until she left for work, after dinner. I took her car keys and drove her Jeep over to Nadel’s House of Clocks.

Nadel was in the workshop behind the showroom. He had thick, magnifying glasses strapped to his mostly bald head and was bent over a vise, filing a groove into a steel rod the size of a pencil. The shop smelled like iron filings and machine oil.

“That you, Seth?”

“Hey, Mr. Nadel. What’re you working on?”

“An old Waltham wall clock. Eight-day regulator. Not worth the price of the repair, but the lady said it has sentimental value.” Nadel had lived in the States for forty years, but his German accent was still heavy. “Sentimental to her, maybe. To me, its value is rent money.”

“You wanted me to pick something up?”

“Yes, the address is there on the workbench, by the drill press.”

I found a scrap of paper with the name Lear and an Old Town address on it. A nice neighborhood.

Nadel looked at me with a tilt of his head. “They had their maid call. Real Richie Rich types, so use your manners when you go.”

Nadel paid me twenty bucks for a pickup or delivery. It was easy money. Nadel didn’t like driving, so he was as happy to pay it as a miser like him could stand to be. I drove from his shop to Heath Way, took a left before I reached the high school, and followed Tacoma Avenue past the Lawn and Tennis Club.

The Lear house was set far back from the road. It had a lawn big enough to land a small plane on and came complete with water features and statues of children playing—statues as nice to look at as real kids, but without all that annoying life and breath.

I climbed about one hundred steps to the front door, then lifted the heavy knocker and let it fall. A Latino woman in a starched white uniform opened the door.

“Are you for the clock?” Her accent was Mexican, but more carne asada than taco truck.

“I’m for it, if you are.”

She gestured to come inside. “Please.”

“Thank you.” We had all the politeness covered and she walked across an entryway about the size of my high school gym. I could hear her shoes echo down a hallway and hoped she’d come back sometime that day.

I looked around. The entryway ceiling must have been twenty feet high. A huge crystal chandelier hung halfway down, but the only light came from an arched doorway that led into another room. Peeking around that doorway was a sliver of a girl’s face. All I could see was an eye and a waterfall of dark brown hair, but if the rest of the face matched, it was probably lovely.

“Nice place you have here,” I said to the face.

The face stepped into sight, followed by a body that was equally lovely, dressed in a black tank top and a short denim skirt. It was a body that kept in shape playing on elite soccer teams and dancing with honor students. I’d seen her before at school—she wasn’t the type you forget—but I didn’t know her name. She hung around the rich kids. If I remembered correctly, she spent a lot of time on the arm of Erik Jorgenson, one of the Heath High royalty.

“Yeah, real homey,” said the girl, in a voice that surprised me with its hint of roughness, as if she’d yelled too much as a kid. “You can hear your echo, because it’s that big and empty. I’ll trade you anytime.”

“If you saw my apartment, I don’t think you would.”

“You have an apartment? Where?”

I laughed. “I’m not telling you where I live. People from your part of town can’t be trusted.”

“You don’t really have an apartment, do you?”

“You say apartment like it’s something exotic. It’s a room with a bed in it.”

“Sounds dangerous. Tell me where it is.”

I gave in. “You drive your daddy’s BMW down K Street until it crosses Division and the street name changes to Martin Luther King Jr. Way. That’s how you know you’ve entered my neighborhood. They don’t honor Martin on your block, because it’s bad for property values. You keep driving until you pass Hilltop Pawn Shop. On the next block, you’ll see a big red sign that says Boxing. Click your remote until the alarm chirps, then go inside the boxing gym. When ChooChoo and the other men in there see someone who looks like you, they might teach you a few new words, but just ignore them. Head all the way to the back, by the rusty boiler, and go up the stairway there until you come to the only door. That’s the door to my home. Kitchen, bed, and TV all in one handy room. The whole place would probably fit in your bathtub.”

Her big eyes opened even wider. “How old are you?” she asked.

“Old enough. Sixteen.”

“Me, too. I’ve seen you before. You go to Heath High, don’t you?

“Yes. Look, I got things to do. Any chance you could help the señora find the clock so I can get out of here?”

She didn’t move, except to stick out her bottom lip.

“What’s your name?”

“Seth.”

>

“That’s right. Seth. And you have a funny last name, if I remember right. What’re you doing this Friday?”

“Why? You need someone to mow your lawn?”

“I’m going to a party, and Janine would totally flip over you.”

“Yeah, that’s my job. To make Janine flip. Look, umm—”

“—Azura—” She seemed suddenly self-conscious when she said her name, bringing her chin down so that she looked at me through her eyelashes.

“Azura? Azura Lear? Sounds like a brand of luggage. Look, Azura, I’ve never been very good at parties. I think I’ll just take the clock and go home, if that’s all right with you.”

“It’s not.” She got up and walked slowly away, sashaying her denim skirt back and forth as she went, leaving me in the faintest wake of a soft perfume. She was like a walking permission slip. She turned once when she reached the hallway and tapped her finger on her lips. I couldn’t tell if she was trying to think of something to say or asking me to keep quiet. She turned away again and sashayed out of sight.

The housekeeper came back with a cardboard box containing the clock. I left, giving her a Gracias, señora, just to show off my bilingual skills.

Two

Nadel was still bent over the tiny metal rod, filing away, when I came in with the box. Mom had been cleaning his shop since I was a baby. When she first started, she worked in the daytime and often brought me with her. Nadel complained at the beginning. “Fraulein, this is no place for babies. All the parts for choking. And baby noise is a noise I cannot work around.” But Mom explained that I was a different kind of kid. I kept quiet and wouldn’t get into things.

Mom told me that I used to sit and watch Nadel work for hours without making a sound. Pretty soon, Nadel was giving me oily tools to play with and letting me dig through boxes of broken mainsprings and worn-out escapement gears. By the time I was in third grade, I could fix most simple pendulum clocks, with a little help from Nadel.

Nadel taught me that many things people think are fragile, like antique clocks, are actually pretty tough. And almost everything can be fixed. “My customers—they should be careful. If they break it, it costs them money. But me, I shouldn’t worry about careful. If I break it, I fix what I break and charge them extra.” Nadel knew he could fix anything. So I smiled when he grabbed the box from me and set it on his workbench with a clunk, as if it contained a piece of scrap metal instead of an antique.

“How was the house?”

“Big.”

“Who answered the door?”

“The maid.”

Nadel nodded. He opened the box and hauled out a pendulum wall clock, about three feet long and shaped like a chunky banjo. “An old one,” he said, walking his fingers along the burled wood of the case. “Early 1800s or even late 1700s. A Simon Willard—see the signature? Look at the joints. Perfect. And gold-plating, though it’s mostly worn off the lens frame. Wonder if they want me to replate it.” Nadel could do anything required to fix a clock. With his store of chemicals and the skills of a metallurgist, he could restore the gold or silver-plating on a clock face. With the hands of a machinist, he could craft steel parts from scratch. He hung the clock from a peg on the wall, leveled it with a practiced squint, opened the case, and gave the pendulum a swing. It swung once and stopped.

Nadel pulled the clock off the wall and laid it facedown on a shop towel. The back of the beautiful old clock was as plain and unvarnished as the underside of a kitchen table. Nadel casually pried a panel off the back with a screwdriver and looked inside. He frowned, then pulled out a crumpled, folded, yellowed piece of paper. “Rich people using a clock case as a recycle bin.” He tossed the paper toward a distant trashcan and only barely missed. Without replacing the panel, he hung the clock back on the wall and gave the pendulum a swing. The clock ticked happily away.

“That didn’t take long. You want me to bring it back to the Richie Rich house?” If I had to, I figured, I could force myself to see that girl again.

Nadel scowled. “Are you crazy? Maybe in a week you’ll bring it back. Maybe two weeks. Lear can afford more than fifteen minutes of my time, Seth. And this clock is worth a hefty bill. A maid who answers the door? A Simon Willard? I’m trying to keep open my business and you want to bring the clock back in fifteen minutes?”

I left Nadel to his creative invoicing. I walked through the ticks and tocks of his showroom and drove the six blocks to Shotgun Shack for a bite to eat. “Oh My” by Sweatshop Union had played only halfway through when I parked, but the song was so good I had to sit and listen to the whole thing.

We need food, clothes, and shelter,

So we hustle till we’re old and helpless,

And if you do only go for the gold and wealth,

You’re still alone ’cause you don’t know yourself…

By the time the song ended, my mouth was watering for Miss Irene’s cornbread stuffing. I walked inside the restaurant. Mismatched wooden tables were carefully arranged by Miss Irene to fit in as many customers as possible. A good thing, since Shotgun Shack was standing-room-only most nights and weekend mornings. The black-and-white linoleum floor was worn but clean. A counter was faced by a row of bar stools. Behind the counter stood Checker Cab, a big, soft, black man whose mouth hung open, even though he always breathed loudly through his nose.

It was mid-afternoon, so the restaurant was mostly empty. Stanley Chang, an old Hawaiian whose full legal name was about a million syllables long, sat at his booth by the front door, pouring over a battered copy of the Tacoma News Tribune. Stanley Chang wore colorful silk shirts, even if the rest of his clothes were old and worn. Today he had on a dark red shirt with gold leaf patterns on it. It didn’t match the tweed sports coat he wore over the top of it, but, man, that shirt was sure something. The jacket was too small for Stanley’s big belly, but that put more of the beautiful shirt on display.

Stanley Chang said he came to Shotgun Shack for the catfish and greens, but no one believed him. Southern soul food was never real big in Honolulu, where Stanley grew up. Everyone knew that what really brought Stanley there were his feelings for Miss Irene. Stanley Chang was sweeter on Miss Eye than the cane syrup on her corncakes. She’d come over to his table—she waited on him personally whenever she could—and he’d straighten the collar of his shirt and say, “Mahalo, Ko`u Ku`u Lei” in a slow island drawl. And she would giggle and say, “Stanley Chang, you better cut out that tropical talking or I might just accidentally fall in your lap.” She’d laugh, but Stanley would just stare at her with his dark, hungry eyes.

Back in the corner, King George talked loudly into his cell phone. George was only a year older than me, but seemed to take up twice as much space. Back in middle school, he’d been something like a myth used to scare sixth graders. You’d better be cool, an eighth grader might have said, or King George will murder you on your way home. And he really might have. George had been in and out of juvie at least three times that I could remember.

King George had dropped out of school when he was fourteen. Nowadays, he always had a roll of cash as big as a fist jammed into his pocket. If anyone ever asked where he got it, King George would just give them The Look and they would stop asking. The Look said, “Ask me again, and I will inflict great pain on your body.”

I figured Miss Irene must be particularly scared of George, even though George was only seventeen. She complained about him constantly and quietly back in the kitchen, but she let him hang out in the restaurant as long as he wanted, even when ten customers were waiting for a seat.

As far as I could tell, King George only did three things: sat in Shotgun Shack eating rib-eye steaks, lifted weights to keep his arms as big as my legs, and rode around town on his black BMX bike. He couldn’t get his license until he turned eighteen, because he’d never gone to driving school. For a while, he’d driven around a black Lincoln SUV, but the cops had pulled him o

ver a couple of times and finally impounded the car. King George made that BMX bike look small.

At Shotgun Shack, King George would shout his meat orders across the restaurant. “Miss Irene! I want me a rib-eye and a brisket!”

“What you want to drink?”

“I want a protein shake, but since that seems to be too complicated, get me a black coffee and a glass of milk.”

“You should eat a salad or some fresh fruit,” Stanley Chang would say, glancing over the top of his newspaper. “All that meat and no roughage plug you up.”

“You better shut up, old man, or you gonna feature prominently in my evening workout.” Stanley, who was probably fifty years old, would duck behind his newspaper like a kid playing peek-a-boo and King George would grumble and fuss until a few pounds of meat were set in front of him.

That day, when I walked in, Stanley Chang said, “Aloha, makamaka. How are you today?”

“Hey, Stanley.”

“That Seth?” shouted Miss Irene from the kitchen. “Slugger, come on back here and help me fill an order or two.”

I’d always loved cooking with Miss Irene. Mom had never cooked much, but hanging with Miss Eye in her kitchen felt like mom-time to me, even if we were cooking for customers instead of family. Miss Eye said I was a natural in the kitchen. I liked the process of cooking. Order mattered. Amounts mattered.

Miss Irene acted like she needed my help, even though I knew she worked faster when I wasn’t there. I’d been cooking on that grill and in those fryers for quite a few years, but I still couldn’t keep up with the movements of Miss Eye. Every motion of her hand accomplished something. She could crack an egg and separate the yolk from the white with one hand, dumping the white into a bowl for a lemon meringue pie and using the yolks for an egg wash for her fried chicken.

She told me to clean my hands, then asked me to mix up her secret seasoning salt with some flour, garlic powder, and black pepper. I measured the ingredients and stirred them together with my still-damp fingers, the white flour filling in the cracks of my knuckles. Once I was done, I started dipping chicken parts into the egg wash, then coated them carefully in the flour mixture, then back in the eggs, then back in the flour and into the fryer basket.

The Tilting House

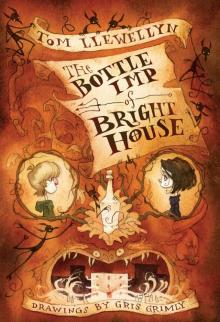

The Tilting House The Bottle Imp of Bright House

The Bottle Imp of Bright House The Shadow of Seth

The Shadow of Seth