- Home

- Tom Llewellyn

The Tilting House

The Tilting House Read online

Text copyright © 2010 by Tom Llewellyn

Illustrations copyright © 2010 by Sarah Watts

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Tricycle Press, an imprint of Random House Children’s Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. www.randomhouse.com/kids

Tricycle Press and the Tricycle Press colophon are registered trademarks of

Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Llewellyn, Tom (Thomas Richard), 1964-

The tilting house / by Tom Llewellyn ; [illustrations by Sarah Watts]. — 1st ed.

p. cm.

Summary: When Josh, his parents, grandfather, and eight-year-old brother move into the old Tilton House, they discover such strange things as talking rats, a dimmer switch that makes the house invisible, and a powder that makes objects grow.

[1. Dwellings—Fiction. 2. Eccentrics and eccentricities—Fiction. 3. Family life—Washington (State)—Fiction. 4. Rats—Fiction. 5. Human-animal relationships—Fiction. 6. Washington (State)—Fiction.] I. Watts, Sarah (Sarah Lynn), 1986- ill.

II. Title.

PZ7.L7724Til 2010

[Fic]—dc22

2009049275

eISBN: 978-0-307-78080-5

v3.1

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Three Degrees at 1418

The All-the-Way-Up Room

Mr. Daga

The Vultures

Grandpa’s Wooden Leg

The Attic

The Box

Moss

The Dimmer Switch

Mrs. Natalie’s Little White Dog

The Story of F. T. Tilton

The Mother Lode

The Black Sack

The Talker

Body and Soul

The Name on the Sign

Acknowledgments

THE WOODEN SIGN on the porch read TILTON HOUSE.

“Why’s it called that?” I asked. No one knew. Not even the real estate agent, Mrs. Fleming—though the way her hands were shaking made me wonder if she was hiding something.

We were all standing in the house’s front yard next to an overgrown holly tree that reached higher than the rooftop.

“Fourteen eighteen North Holly Street,” said Mom, looking over the information sheet. “This is the cheapest house in the neighborhood, even though it’s got to be one of the biggest.” Mom looked up at the agent. “What’s the deal?”

“Maybe we should go inside before I answer that,” said Mrs. Fleming. “The previous owner was a bit eccentric.”

“It’s a classic,” said Dad. “Looks like a custom design. It’s got a nice big front porch, and it’s in a decent neighborhood.”

My little brother, Aaron, and I glanced at the house next door when Dad said this. Boards covered most of its windows.

The house in front of us wasn’t in much better shape. The two windows on the second floor and the sloping roof over the porch made me think of a gray old man with a drooping mustache.

Half an hour earlier, I would have said that any house was better than the cramped apartments we’d called home my whole life. Now I wasn’t so sure.

“It needs paint,” Mom pointed out.

“So we can paint it,” said Dad. “What’s your favorite color? Josh and Aaron’ll help—won’t you, boys?”

“Can we paint it today?” asked Aaron.

“See?” said Dad. “The boys are excited.”

“I’m not,” I said. “This place looks like a dump.”

“Quiet, Josh,” Dad said quickly.

“You’d only be the second owner,” Mrs. Fleming chimed in. “The original owner lived here more than seventy-five years.”

“Oh, is he …?”

Mrs. Fleming nodded. “Yes. He passed away just recently.”

“A dead guy lived here?” Aaron asked me in a whisper.

“Before he was dead,” I replied. “Not after.”

“Oh. Good.”

“Who’s that man across the street?” asked Mom. “He’s staring at us.” On the front steps of the well-kept old home opposite sat an elderly man. He was looking right at us and his lips were moving, but from where we stood we couldn’t hear what he was saying.

“I’m sure he’s harmless, honey,” said Dad. “Anyway, you’re the one who’s always saying you’re sick of living in apartments. This is our chance! There is no way we could afford another house like this.”

“Well, let’s look inside,” said Mom. “But there’s got to be a reason it’s so cheap.”

We followed Mrs. Fleming up the front steps. She unlocked the door and placed a shaky hand on the doorknob. Then she hesitated and turned to face us.

“Now, it may be a bit … unnerving when you go inside, but remember what a good price this is. And remember what wonders a coat of paint can do.” She smiled weakly and opened the door.

We walked inside and the world tipped.

Aaron fell against me.

“Watch it!” I said.

“I can’t help it!”

Mrs. Fleming sighed. “The floor tilts three degrees precisely. If you’re thinking the house is settling, it’s not. It’s as solid as a rock. The house was built this way and I can show you the original blueprints to prove it.”

“You mean the whole house is like this?” asked Mom.

“I’m afraid it is. Every room.”

“Why would someone design a house with tilting floors?”

“I don’t know,” said Mrs. Fleming, checking her watch. “It’s a bit of a mystery.”

“Cool!” said Aaron. I glared at him and took a few steps into the hall.

A ray of sunshine streamed through the open doorway, lighting up swirling particles of dust. As my eyes adjusted to the dimness, I noticed something. Words, numbers, diagrams, and drawings scribbled in pen and pencil covered the walls, the railings, and most of the floor.

“Walls are easy to paint,” Mrs. Fleming said, following my gaze.

“I wouldn’t dream of painting it,” said Dad softly. He walked lopsidedly to the nearest wall. On the faded rose-patterned wallpaper, the words quadratic ionization, were written in spidery script next to a drawing of a cone-shaped device. Wires connected the cone to the ears of a beautifully drawn and detailed human head. A chart of numbers next to the head was labeled amplified bioacoustics.

“It’s strangely beautiful,” Dad said. “Honey, this could be an important work of outsider art. The museum should know about it.” He turned back to Mrs. Flemming. “Was the owner an artist?”

“I don’t know. None of the neighbors ever met him.”

“I thought you said he died just recently.”

“He kept to himself,” said Mrs. Fleming. “That’s what the neighbors say at least. But neighbors say a lot of things.” Her hands were shaking harder than ever. “I can drop an additional ten thousand off the price if you make an offer today.”

“No one ever met him?” I asked.

“I’m sure someone did.” She put her hands behind her back. “Look, I understand if you’re not interested. I’ve shown this house over twenty times and no one’s ever gone past the entry. Just say the word and we can go our separate ways. No hard feelings.”

“I never said we didn’t want it,” said Dad. He turned to Mom, who was shaking her head. “Give it a chance, hon. This house could be a serious artistic find. Look at the detail on these drawings.”

“They look like they were drawn by a crazy man,” Mom said.

“People thought Van Gogh was a crazy man.” Dad was trying to win her over—Van Gogh was Mom’s favorite artist. “And look at the trim! It’s probably cherr

y.”

“Actually, it’s holly,” said Mrs. Fleming.

“Did you hear that? Holly! Holly trim on Holly Street. What other house has holly trim? Look at the carving on this stairway. And what about these original wood floors?”

“I saw them. They’re all tilting.”

“Okay!” cried Mrs. Fleming. “I’ll drop the price by twenty thousand, but that’s as low as I can go!”

“It’s not low enough,” I piped in.

“Josh!”

We bought the house. For that price, Mom said she could get used to the tilt and the scribbles. I think she realized that Dad was right: We’d never be able to afford a house half as big on Dad’s art museum salary and the money Mom made working part time at the school office. We were doomed to live in a dumpy, tilting house.

Two weeks later, on the first day of summer vacation, we moved in: Mom, Dad, Grandpa, my brother, Aaron, our cat, Molly, and me. We left behind a two-bedroom apartment across town, where my parents had one bedroom, Aaron and Grandpa the other, and where I had slept on the living room couch.

On moving day, while the rest of us hefted boxes, Grandpa eased into the porch swing and pulled out his pipe and tobacco pouch. His wooden leg made him kind of wobbly, so he sat puffing and directing traffic.

Aaron and I stopped a moment to rest on the porch. Grandpa ran his hand along the carved armrest of the swing. “This is fine craftsmanship. Some of the best I’ve seen. I can tell that this porch swing and I are gonna be good friends,” he said. “Now I can smoke even when it’s raining.”

He leaned back and then pointed his pipe stem at the man across the street—the same old man we’d seen before. “Interesting gentleman over there,” said Grandpa. “He’s been sitting jabbering to himself for the last half hour.”

Later that afternoon, after we’d unloaded most of the boxes, Mom dragged Aaron and me over to say hello to our new neighbor. He looked even older than Grandpa. His white hair was combed straight back. His face was deeply wrinkled, and thick eyebrows nearly hid his eyes. Weirdly enough, though, his clothes looked freshly ironed.

The man didn’t look up when we got to his porch. He just kept muttering to himself.

“Maybe he’s hard of hearing,” said Aaron. “HELLO! WE’RE YOUR NEW NEIGHBORS!” The Talker—that’s what we later named him—continued to stare straight ahead at our house.

“She may have been the rawest and most unlettered of the talking picture stars,” he mumbled. “The entire contents of the box had escaped. Only one thing remained.” Then he said something about a place called St. Hubert and “a dead Belgian with staring eyes.” Mom pushed us along as we walked quickly back across the street.

Immediately to the south of our new house sat a duplex. There were two mailboxes and two front doors—one leading to the upstairs apartment and the other to the downstairs one. Nobody lived in either. The grass needed mowing.

To the north sat the house with the boarded windows. Faded sky blue paint was peeling off its remaining shingles. A purple front door was buried behind wagon wheels, stuffed animals, old mailboxes, and a huge set of deer antlers. The grass needed mowing there, too.

The man who lived in the house with the purple door had a mop of greasy gray hair and wore flip-flops, shorts, and an unbuttoned Hawaiian shirt. He glared at Aaron and me on moving day when we said hi to him.

“Keep it down.”

“Keep what down?” I asked.

“The noise.”

All the other houses on our block had fresh paint and neat yards, and the neighborhood overall seemed pretty normal.

But the only other kid our age who lived on Holly Street told me it wasn’t. Her name was Lola. She lived in the green house on the corner with her mom and stepdad. She was a year younger than me, but taller by at least three inches.

“It’s definitely not normal around here,” she said, twirling a strand of curly dark hair. “And you’re living in the weirdest house of all. Everyone says so. The tilting floors are just the beginning.”

“What do you mean?” I may have agreed that our new house was weird, but I didn’t like her saying so.

She shook her head. All she would say was, “No one’s seen the guy who lived there for sixty years. And my stepdad says you have rats.”

Lola was right. We found the rats the very next day. The day somebody died in our new house with the tilting floors. Somebody named Jimmy.

MOM HAD HOPED that Dad would change his mind and paint over the walls before we moved in. I’d hoped so, too. There was no way I was going to invite friends over to this place with the walls looking like that. But they remained covered in cryptic writing as we unpacked boxes in the kitchen. “I’m not going to be happy if I have to live with all these scribbles,” said Mom.

“Don’t think of them as scribbles, honey. Think of them as art,” said Dad. “The man was probably a crazy genius!”

“You need to take down that wallpaper, Hal.”

“First I have to schedule a professional photo shoot. It’s my responsibility as an art curator.”

“When is that going to happen?”

“I’ll put it on my to-do list.”

That afternoon, Dad took a break from arranging and unloading and found Aaron and me in the living room where we were shelving books. Dad plunked down on the couch, and his body leaned to the right. He wiped the sweat off his forehead and let out a sigh. “Guess I’m gonna have to prop up all the furniture.”

I stared at the words on the wall behind his head:

It didn’t look like art to me. It looked like something I was supposed to have learned in school.

“Whaddya say you boys and me take five and poke around a bit?”

“Poke around where?” I asked.

“Around our new house. I’ll bet if we look in every nook and cranny, we’ll uncover a secret or two.”

“A secret?” asked Aaron. “What kind of secret?”

“I don’t know.” Dad grinned as he struggled to get up from the tilting couch. “A house built with tilting floors has got to have secrets.”

“It’s got to have a screw loose,” I said.

“Smart aleck.”

We started in the garage and found a dusty clock tucked away on a corner shelf. We wiped it off and brought it inside to see if it worked.

“Too bad we don’t have a fireplace,” said Dad. “We could set this on the mantel.”

“I’m glad we don’t have one,” said Aaron.

“Why?”

“Because the floors tilt. I might fall into the fire.”

Dad said we needed to find a level surface to test the clock. “It’s not going to be easy in this house,” he said, clearing a moving box off the dining room table and setting the clock down. He started the pendulum swinging, and the clock ticked happily away.

“Hal,” said Grandpa from the other end of the table, where he’d been working on a crossword, “it appears you set that clock down on the one thing in this house that’s not tilting.”

The dining room set had come with the house. Dad figured it had belonged to the previous owner.

“Why doesn’t the table tilt?” asked Dad, leaning down and looking at the legs.

“Don’t you see? The table and chairs were custom made for this house. Look, the legs at that end are longer than the legs at this end. Whoever made them did some excellent work.” Grandpa patted the smooth surface of the table.

“It’s a long shot, but I’ll bet.…” Grandpa slipped out of his seat and examined the underside of the table. “I knew it! Look at this, boys!”

We all crouched under the table. “See this name carved here?”

“Who’s ‘Lennis’?” Dad asked.

Grandpa gave Dad a sour look and pulled himself back into his chair. He rolled up the pant leg to reveal his wooden leg. “This,” he said, “is Lennis. Or I should say, Lennis is the name of the old codger who carved this stump. Best carpenter I ever met. Must’ve made this dining room

set, too.”

“You think this table’s worth something?”

“Only to someone with tilting floors.”

“We ‘ve got plenty of those,” I said.

Dad wanted to look in the crawl space under the house, so Aaron and I followed him outside to a three-foot-high door under the back porch. We unlatched it and looked inside. Spiderwebs stretched across the doorway, with nothing beyond but darkness.

“No way am I going in there,” I said. “You go, Dad.”

“I bet no one’s been down here in fifty years. Maybe we can find out why this house was built with tilting floors.”

“Close the door,” said Aaron. “I don’t like it.”

“Me neither. Can we just finish unpacking?” I asked. I could feel goose bumps on my arms and legs.

“Aww, come on, you scaredy-cats,” said Dad. “This is uncharted territory.” He ducked and found a light switch. A yellow bulb cast shadows across the crawl space. Dad hunched inside, batting cobwebs as he went. Aaron and I stood in the doorway, as still as stones.

“Nothing but dirt,” Dad called back to us. The cobwebs frosting his hair made him look old, like Grandpa.

We went back into the house. In the second-floor bathroom we found a cupboard next to the toilet. Mom came in with a box of cleaning supplies and asked Aaron and me to put them in there. While Dad continued searching the house, we hurried to fill the cupboard with scrub brushes, spray bottles, and rolls of paper towels. We slammed the door and heard a scream from the floor below.

Aaron and I ran downstairs to find Mom standing in the laundry room, rubbing her head gingerly. Paper towels and bottles of cleaner lay scattered at her feet. We all looked up and saw an open trapdoor in the ceiling.

I ran back upstairs and opened the cupboard. It was empty now.

“Heads up!” I yelled and tossed a pink washcloth in the cupboard. I closed the door, then opened it. The washcloth was gone. When I raced downstairs again, the cloth was resting crookedly on top of Mom’s head.

The Tilting House

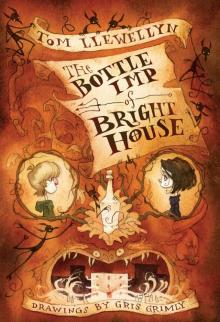

The Tilting House The Bottle Imp of Bright House

The Bottle Imp of Bright House The Shadow of Seth

The Shadow of Seth